Until now, we have been accustomed to thinking of a building as a parallelepiped standing on the ground and covered by a roof. From this extreme and imaginary schematization comes the idea that any architectural structure has four façades, plus an invisible side consisting of the basement resting on and including the ground, and another, the roof, facing the sky. This latter has the job of protecting the contents of the building from external agents like rain and snow and, from the earliest times, theorized in the 18th century by Laugher, who introduced the model of the primitive hut, the roof has always been viewed differently from any other side, conceived as tilted downward from a peak, or domed, and made of particular materials such that its construction gave rise to significant forms of specialization. Whether made of terracotta tiles, ceramic, stone or wooden shingles, historically rooftops were inhospitable places, hard to reach and complicated to build, yet there have always been attempts to inhabit them, as seen by the Venetian sunroofs suspended on tile as little terraces or airy rooms with a view. With Le Corbusier, in one of his five commandments, he prophesied the “roof garden” as an area to use to expand the area of the home, thereby introducing a concept that has proven to be extremely useful in our own time although, we have to observe, in most cases, the use made of the space has been very different from the noble intentions of its originator: flat roofs have often been used as platforms for a series of systems that continues to grow. We have gone from the handsome rooftops in tile that characterized urban skylines before the war, to flat concrete slabs often cluttered with the machinery, vents and cisterns necessary for the operation of modern sanitary and air-conditioning systems which, though they smaller and less intrusive on residential structures, can be utterly devastating atop office buildings or large commercial structures.

The latest electronic era gives us the opportunity to return to think of the roof as a habitable place once again, and there is, indeed, a necessity to do so, for many reasons, the primary of which is the desire or need to limit soil consumption and thus to make even the fifth side of the cube habitable. It is fostered by the awareness that in new buildings the systems can be designed in such a way as to integrate with the building itself, with the technical portions identified and positioned in less noble parts of the building, such as the underground areas. Sub-roofing, attics, etc. are also places that benefit from views and are therefore worthy of particular attention, as they have high added value. Whenever possible, the rooftop can expand the public space or, covered with earth and green plants, serve to re-naturalize the built land, offering the opportunity to restore to the natural landscape those areas occupied by the construction below it. There have also been, and continue to be, many experiments regarding the installation of greenery vertically, fastened to the sides or climbing up them, but speaking sincerely, it seems that the entirely unnatural effort appears disproportionate with respect to the benefits. Perhaps it would be better to leave to the façades their normal tasks and to the rooftops, more in the modern view, their own. In other words, let’s live on them and grow things on them. To use them just as containers of machinery is a real waste.

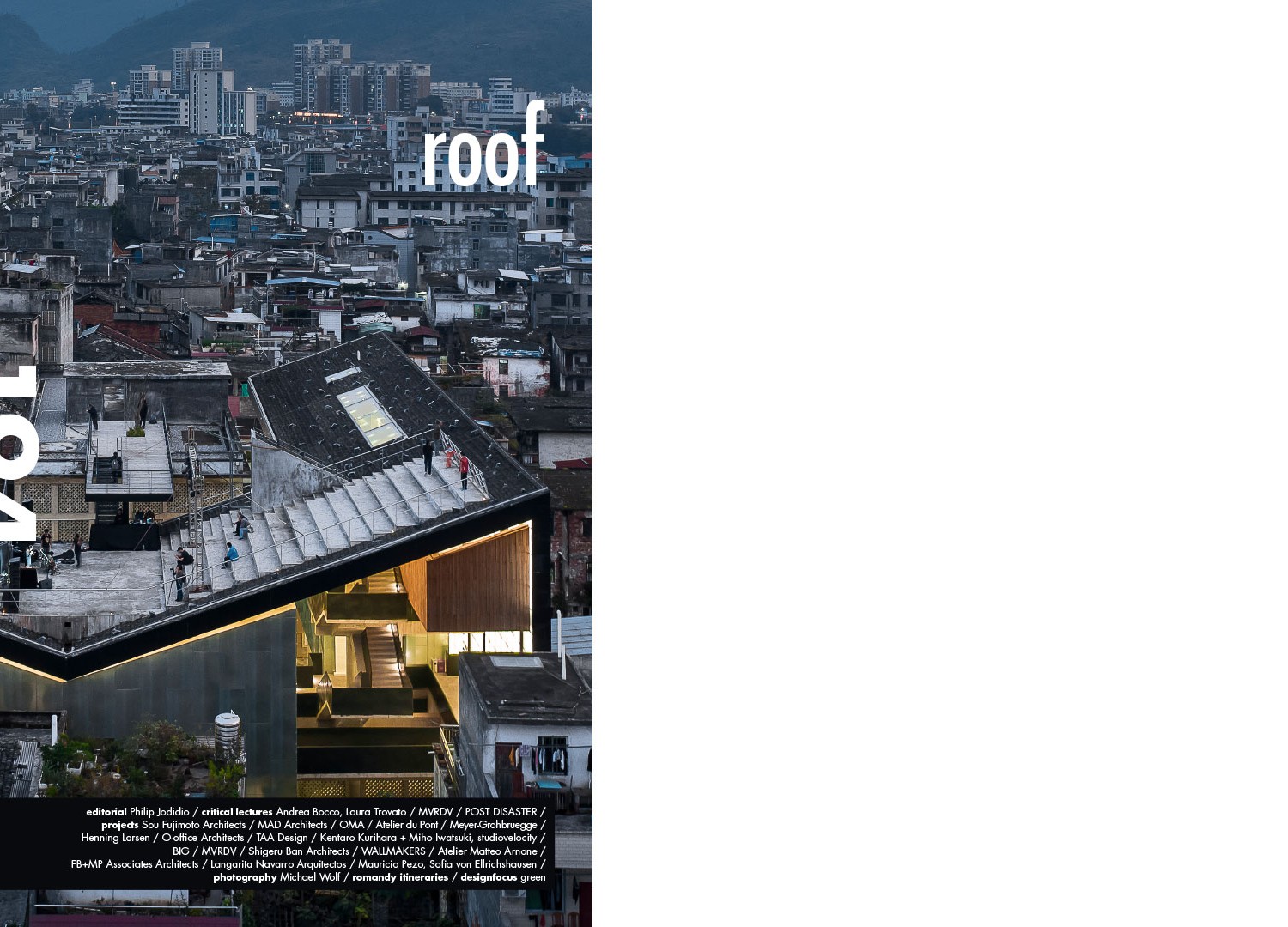

Download cover

Download table of contents

Download introduction of Marco Casamonti