International magazine of architecture and project design january/february 2021

100 years of Tirana

After Florence, Tirana is the city I know best, but in actual fact, in Tirana there is a lot of Florence. I perceive Florence in its urban structure warped along a cardo and a decumanus formulated by the Roman architect Armando Brasini but completed by the Tuscan Gherardo Bosio. I perceive it in the design of its main buildings again designed and conceived by the contemporary Florentine master of Giovanni Michelucci but unfortunately deceased long before him, at just 39 years old, in 1941. In Tirana Bosio manages the Central Office for urban planning and he brings with him as a collaborator the engineer Ferdinando Poggi, nephew of Giuseppe Poggi to whom we owe the image and substance of Florence, the capital of Italy. But it is not in the names of the protagonists that a piece of Italy is consolidated and takes shape on Albanian territory, but in the transfer of urban genetics that makes the capital of Albania, which became such on the 11th February 1920, familiar to every Italian visitor who recognizes the identity traits derived from its own physical consistency and morphological characteristics that are common to all those Italian cities, and are many, transformed during the years of Fascism. In Tirana the monumental order of the EUR of Rome is recognizable where the central perspective winds along an axis that shifts from the central Skanderberg square to the terminal Mother Teresa square on the backdrop of which the white travertine of the building of the former Casa del Fascio stands out, now the university seat of the Polytechnic School. Overlaid on these perfectly perceptible foundations were the few public buildings of the communist period from 1946 to 1991, a large number of small pauperist parallelepipeds of vaguely Soviet inspiration, and subsequently a shapeless mass of speculative buildings built chaotically after the fall of the dictator Enver Hoxha until the early 2000s.

But in today’s Tirana other decisive regenerative actions are clearly distinguishable which correspond to the banks of the small river Lana today, characterized by two green embankments, but which a few years ago were a symbol of the unbridled race to wild illegality, which had brutally built even inside the riverbed and several remembrances of the painted façades of the largest residential buildings, an intelligent attempt to revive, with just a few resources, the make-up of a city struck by poverty and constructive bulimia at the beginning of the millennium. Both of these two strategic actions, the total demolition of illegal buildings along the river and the “painting of the façades” are the result of the cultural action carried out by the then Mayor Edi Rama (from 2000 to 2011).

To him we owe much of today’s Tirana and in particular the strategic intuition of organizing architectural and urban planning competitions and of inviting some of the best international architects and artists to participate. What strategy Rama has pursued is all too clear and evident; on the one hand, the belief that the city needs new icons and monuments as well as the creativity of the best players in the world to recover; on the other, the belief that local architects have not the strength to oppose the aggressiveness of the few new rich Albanians to whom after decades of poverty it is not easy to expect awareness on a cultural level with respect to the necessary urban regeneration activity with which a poor state cannot cope with public resources alone. Rama therefore succeeds in an impossible undertaking, that of making the Albanian capital attractive for the best architects worldwide, showing itself as an urban laboratory in which to freely experiment those ideas that have also matured the level of indigenous professionalism crushed by the previous dictatorship and poverty. If we google “Rama mayor”, an erroneous definition appears that portrays him as an ex-artist to whom we owe the famous phrase according to which “being the Mayor of Tirana is the highest form of Conceptual Art. It is art in its purest state”. The error coincides precisely with the first statement since Edi Rama is not a former artist but a fully active artist lent to the cause of his country and, even now that he is Prime Minister of Albania (since 2013), to meet him on Sunday or on his days off from his intense government activity, you have to slip into a shed on the outskirts of the city where together with a master ceramist he shapes and bakes his earth sculptures. Beyond political judgments and personal convictions, the identity of today’s Tirana led by Mayor Erion Veliaj (since 2015) has been nurtured by this artistic and intellectual passion.

He has succeeded in accelerating and continuing the work of modernization together with the strengthening of a renewed urban continuity that manifests itself in the new Skanderberg square, a competition in which I was part of the jury, awarded with full merit and quality by the Belgian architects 51N4E, who wisely pedestrianized and “petrified” it, and with the extension of the main axis of the city designed by the English studio Grimshaw was to mark the development of the new city towards the north.

Naturally, my judgments on the city are marked by an obvious conflict of interests that I would like to make explicit and make as evident as possible, since it is difficult to maintain critical objectivity on a place and events that have marked important moments in my life as an architect.

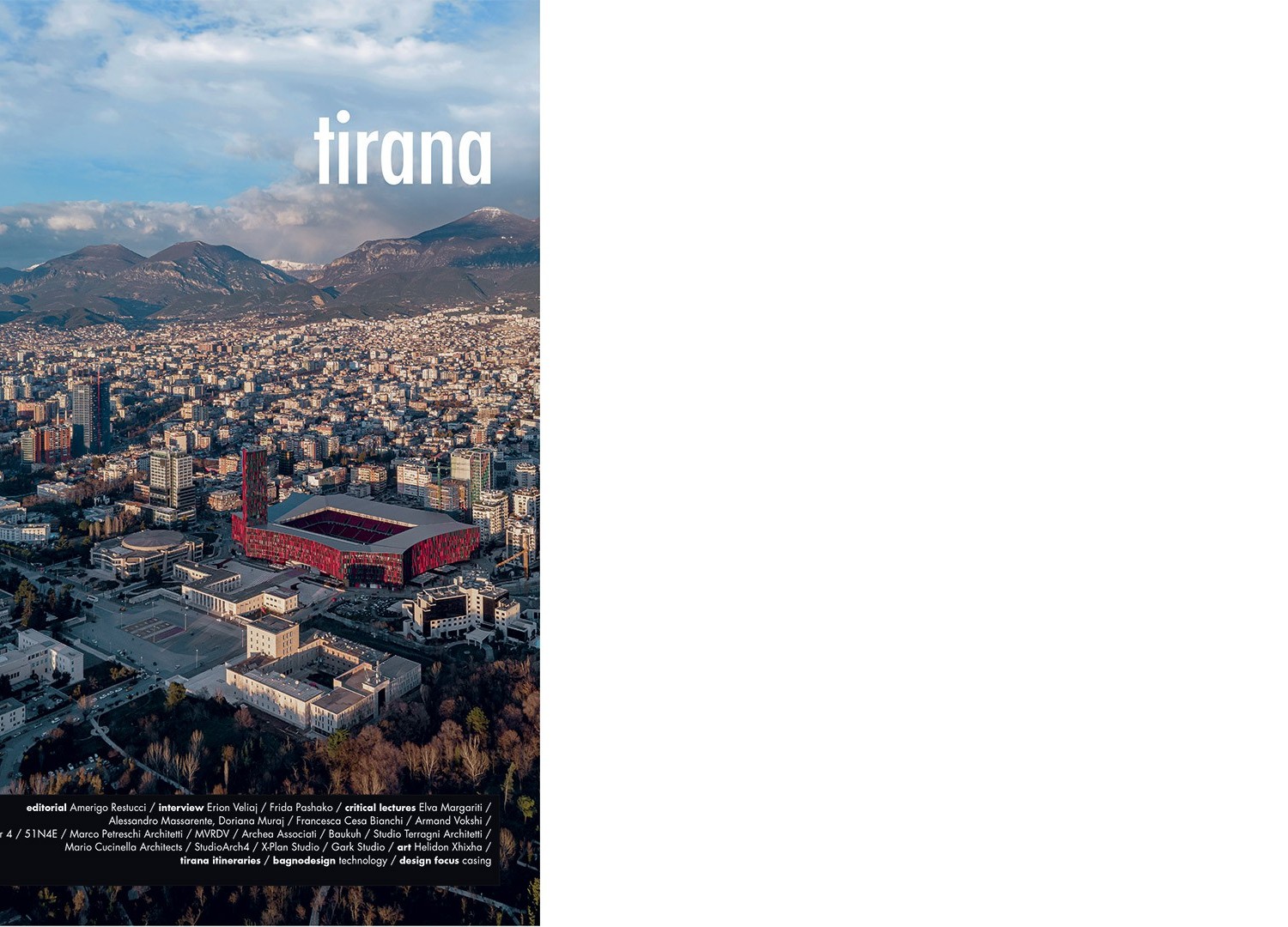

That being said, I do not want to minimize the problems and unresolved issues of the city, its obvious difficulties, but to underline that my deep knowledge of Tirana, its attendance, participation in its transformative processes, the design of its most iconic buildings such as the For ever green Tower, today Alban Tower and the National Stadium of Albania, have built an emotional bond that certainly makes me less inclined to underline so much that still needs to be done compared to the enormity of what has been done so far. Furthermore, in recent years, other Italian architects such as Stefano Boeri who designed the plan of the New Tirana, envisaging an effective green belt to protect and stop unlimited expansion, and the group of young architects, Bauku and Mario Cucinella who will soon create a beautiful building in the city centre, worked by continuing that tradition of an Italian Tirana that undoubtedly interests and involves me. Obviously not everything that happens in an experimental laboratory can be said to be successful but the fact that within several hundred metres you can compare the architectural visions of some of the best known studios globally, from the Big companies involved in the construction of the new theatre, to MVRDV and Winy Mass struggling with an urban giant whose scale we have yet to understand, certainly make the atmosphere of the city as electrifying as few European cities do today. It is obvious that the open questions and unresolved issues are numerous and complex such as the resolution of mobility and traffic problems, the quality of the projects, at times poor compared to the quality of the projects often tampered with for economic and cultural reasons by an entrepreneurial class not inclined to comply with European standards, the enormous cost of land and land rent, the scarcity of resources of the municipality, and the consequent poor quality of services in relation to the main European capitals. All true, but when I landed in Tirana for the first time in 2003 the old airport looked like a bus station and the road to reach the city was unpaved…. And it wasn’t that long ago.

Marco Casamonti

Download cover

Download table of contents

Download introduction of Marco Casamonti

Download “Alban Tower” – Archea Associati