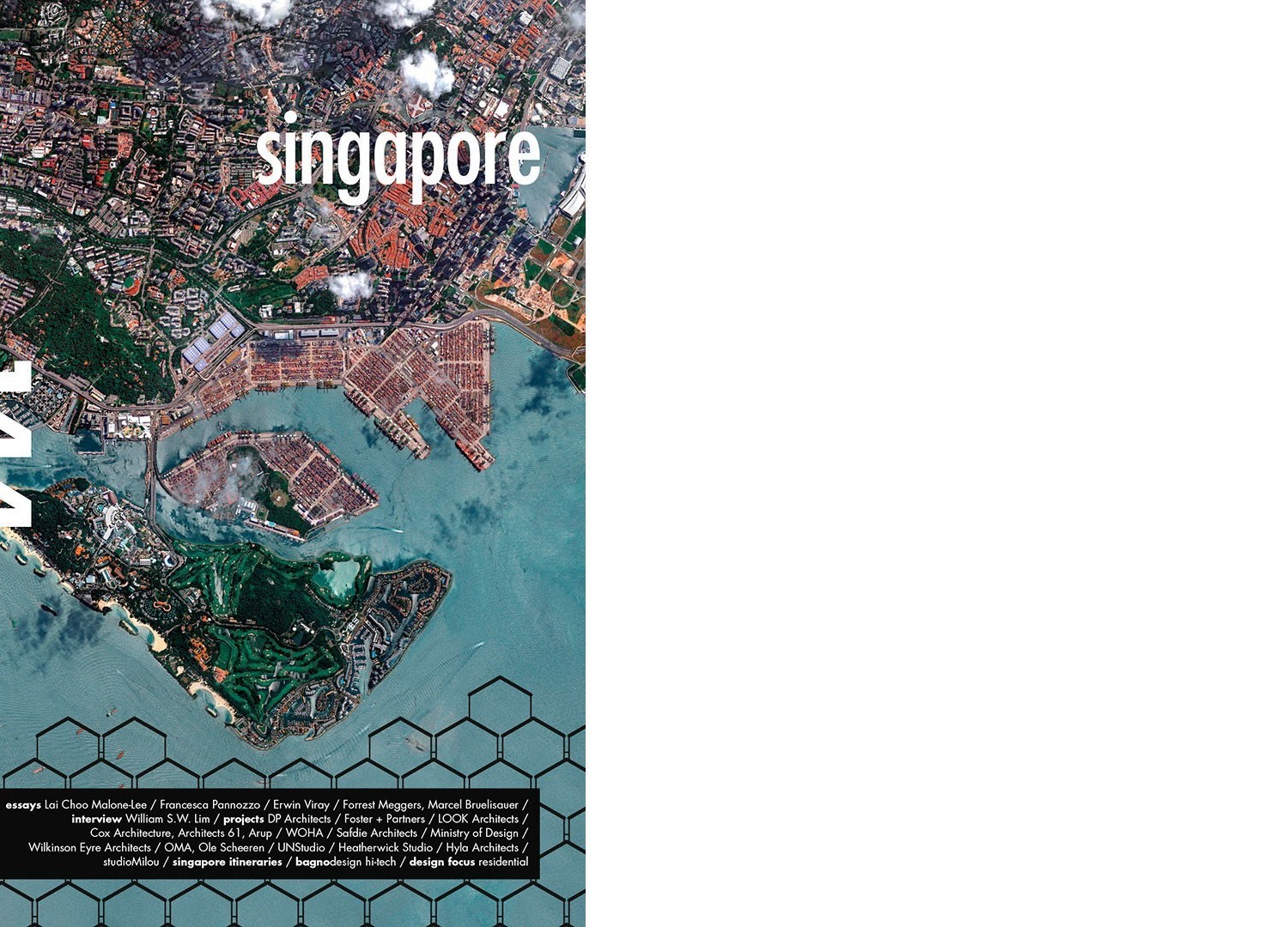

International magazine of architecture and project design january / february 2016

Singapore: Fifty Years of Solitude

Singapore is difficult to define, difficult and complex for its perhaps unique status, a place that simultaneously represents, as in Luigi Pirandello’s famous novel, the disintegration of identity in this case urban in an assembly that can be read, precisely, as One, nobody and a hundred thousand. Singapore is a state, yet also a city; a metropolis, an island, an archipelago; it is one of the most densely populated places in the world, but also a city with extraordinary and immense parks, a totally artificial universe where a system of botanical gardens was built, protected by UNESCO, and considered humanity’s world heritage. Contrary to all countries of the world, its independence does not stem from a voluntary act but by the refusal of Malaysia, which in 1965 renounced legitimate patria potestas, leaving Singapore to a destiny and long-lived, determined political leadership, making it today one of the most important financial centres in the world, a logistic hub which forms the main intersection of trafficking throughout South-East Asia. A rigid democracy where you cannot chew gum, smoke or drink alcohol in public places, where the death penalty is still enforced and individual control very high; nonetheless, it is a country which applies an efficient system of state and justice, where corruption and unemployment are almost absent, with a high standard of living and high average lifespan.

Its architecture, understood as a physical image of the city, as a system of works and monuments, fruit of culture and human activity, is not attractive, it does not strike the visitor, however, compared with a population of just 5 million inhabitants, tourism accounts for more than 10 million visitors each year. This means that its international dimension, built through an anonymous necessary verticality, succeeds in striking the visitor, who does not find, unlike the majority of urban contexts throughout the globe, that sedimentation and stratification of building which commonly defines every idea of the city.

In Singapore, it all happened in the last fifty years and there is nothing original if not the assembly, the model deriving from New York and anticipating Dubai. It does not pursue individual excellence but the generalised marvel of record-breaking gigantism, destined to be surpassed as we have already witnessed with its Ferris wheel, no longer the tallest in the world. Yet this sort of Switzerland of the East, without litter on the ground, as clean as one’s own living room, tidy and functional like the perfect mechanism of a clock, is an exception to other Asian metropolises: multiethnic, desired, rich, perfect.

A metropolis that attracts and triggers reflections and comparisons, stimulating like few others in the world the attention of academics of the city. It is no coincidence that after the famous Delirious New York and Junkspace, Rem Koolhaas has decided to publish an extract from the imposing S, M, L, XL, the booklet Singapore Songlines, an essay revealing the distinctiveness of Singapore in comparison with the rest of the world: It is pure intention; if there is chaos, it is formulated chaos; if it is ugly, it is designed ugliness; if it is absurd, it is a deliberate absurdity. Many factors concur to create the utopia of Singapore, but among the many possible, at least three appear decisive: its solitude, its competitiveness, its continuity in terms of political management, and therefore, of its vision of the world and of life. Ultimately, we cannot but agree with the cited words: it is, in any case, a programmed, entirely intentional phenomenon.

Marco Casamonti

Download cover

Download table of content

Download the introduction of Marco Casamonti